Retrospective

It’s fun to look back.

Daydreaming during the holidays, I had an inkling in the kitchen, so I walked up to the fridge to grab a slip of scrap paper from the magnetic holder. It was on that sheet that I pencil-drafted the UI, filling the blanks with my imagination to create a game that would become Toshe’s Quest II.

On my computer, I still have a folder called tuaold. In addition to a version of the game at a point in time that predates Git history, it holds a few easter eggs. One is a subfolder named 2011 Toshe's Underwater Adventures 2011.

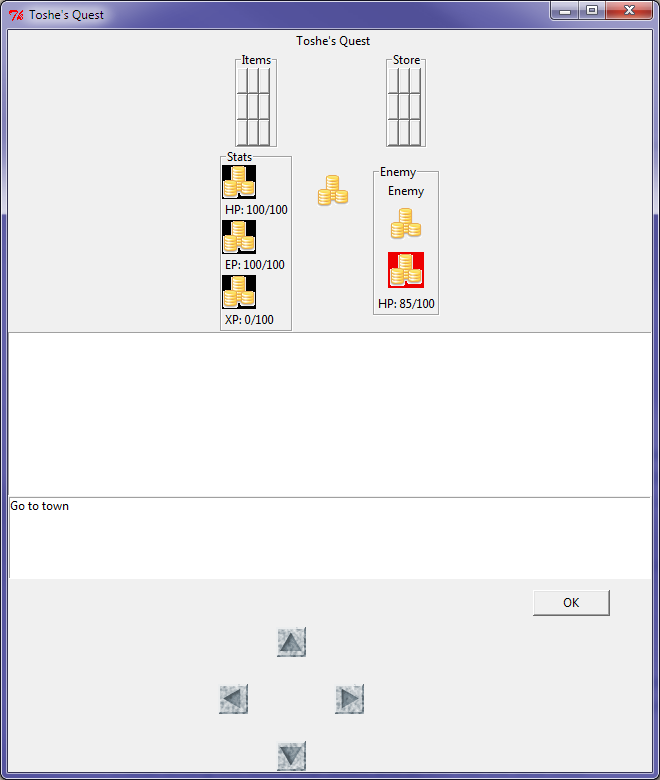

That subfolder is an early prototype of the game. Now, what did that look like?

User Interface

I feel like this was a proof of concept and my way of testing the waters for how I might write an RPG with what I knew about Python and Tkinter.

We have all the general concepts already visible:

- The classic 9-slot inventory

- The store pane

- The concept of money (though not yet represented textually)

- The basic vital stats

- The enemy pane

- The dialogue box

- The options box, with Go to town as a sample option

- Movement arrows

That’s pretty much the game! And the rest seems to be well-documented. That is, for example, if you skim through the UI source code (a meagre 111 lines, compared to the now 3674 lines), you will find that, within the enemy pane, the top image is for the enemy and the bottom is for its HP bar. That’s helpful when the only image is the coins.gif placeholder.

The rest of the files look like boilerplate classes to convey the core attributes of each object.

Areas

What I notice is how the game eventually departed from the initial area concept. It looks like areas started as pure data objects before I realized I needed a more extensible solution, resulting in a full-on class for each area.

I recall writing this strictly top-down, and so this was the data class:

class TUAArea(object):

def __init__(self, name, image, description, choices, directions):

self.name = name

self.image = image

self.description = description

self.choices = choices

self.directions = directions

I hadn’t thought through what types choices and directions would be. Actually, that’s not true, I had, as can be seen from the corresponding areadata.txt with a data sample (tabs converted to newlines for readability):

"The Underbog"

0

"It is sickly in this wretched dungeon. The fumes of green swampwater fill your lungs, forcing you to cough."

{"Fight Undead":undeadbattlemap, "Escape":wilderness}

{True:NorthUnderbog, False:None, True:SouthUnderbog, True:WestWingDungeon}

For the Horde!

Here, we have concrete examples of each attribute value. Except there’s a problem. The choices and directions contain references to undefined objects.

Also, I’d eventually need to fix my wild syntax dreams working overtime. I fashioned the “index” of the directions dictionary to implicitly correspond with a direction (0 → north, 1 → east, etc.), except the indices of dictionaries are not given by their order, but their keys. And the keys themselves were made to correspond to whether that direction is enabled (i.e. True or False), except keys must be unique. You can see how wrong I was going with this approach. With some finessing I may have been able to work around my syntax problems.

That being said, I think the undefined object references problem was a showstopper—it would require some deep nesting to fix in this pure data context.

So areas became whole classes!

Still, one attribute common to all areas was the map.

Map

Here’s the ASCII representation of the Adriatic Sea taken from 2011’s apt mapz.txt:

|_|_|_|e|

|_|_|/|_|

|_|/|_|_|

|_|||_|_|

|x|||x|x|

|_|_|_|_|

| | |s| |

Not that far off from what we ended up with!

It’s convenient that such a logically and visually similar data structure exists to map the concept of a map to its memory representation: the 2-D array. It’s through that sameness that I had the idea of denoting tiles through 4-letter shortforms. That way, everything will be lined up. Why 4 letters? I think my reason was just that it was enough for me to distinguish between any two tiles on a given map. I think though as I started working on larger maps, that became debatable…

Retrospectively, I could have found a good lettercount-font combination that made tiles perfectly square so that I would be able to eyeball a map to determine its relative proportions and accurately eyeball-estimate distance between points. That could have helped with laying things out closer to where they should be before playtesting to save time.

Fun

What’s interesting to me is looking back to see what I found fun. I found making spreadsheets to be a fun activity. Particularly, I enjoyed choosing the names and numbers that represented values of various attributes of items. I can see this from how developed the 2011 weapons spreadsheet is and how many of those weapons made it all the way to the end state. Less fun was picking the numbers for characters. This is clear from the single enemy sitting in monsterdata.txt (Sean).

Enemies vs. Weapons

Thinking back to more recent work on Toshe’s Quest: yes, I found it apprehension-inducing at times to come up with the right combination of stats, skills and loot for a given enemy. The enemy must be at the right difficulty and its attributes must match its “personality” (dictated for example by name, appearance or environment). Part of it is that there are so goshdarn many enemies, and, as you add to the list, you have so many to compare against to verify “do these attributes make sense?”

With weapons, the list is pretty small, and generally verification is mostly important for those sold in stores, and only against weapons sold in the same store. Anomalies are okay if they come down to chance drops. It’s okay for the Lion’s Mane Jellyfish to drop the Fluorophoric Dagger every so often. The player doesn’t know that the jellyfish drops this great weapon at the start. When they do find out, they don’t feel ripped off, they feel rewarded. But, at the shop, if the player is able to see all 9 weapons laid out and compare them, if one stands out as obviously better, they immediately grab that one and that’s no fun. Making choices is fun, but only when they’re meaningful.

The Pundit vs. The Player

So—going back to the gruel of evaluating enemies versus the joy of honing items—how a player reacts to your choices as balancer contributes to the funness of the balancing task.

I guess, from a player perspective, it comes down to expectations. One of the rules of game design is that with challenge comes risk and risk must be rewarded. If a player defeats a difficult enemy, they expect a greater reward than what a Sea Goblin would give.

If an enemy has an unusually difficult stat combination, an extraordinarily powerful skill or just a massive HP bar, the player expects something. Making sure you meet that player’s expectation without giving them too much, and ensuring that what you give them is valuable regardless of the choices they have made until then, is hard.

With items, it’s easy. Each item typically works well for a particular category of player and/or character (e.g. class or role in typical RPGs). A player needs a variety of items and it’s up to them to choose a combination or combinations that work for the circumstances they expect. I guess another part of this is the high agency a player has over item choice versus little agency over enemy selection. And another rule of game design is…give the player agency! The freedom of customization that’s fun for a player makes item design fun for me, too.

What does that say about me?

That affinity toward tweaking numbers in a table—I feel that that persists to this day. Having to manage swathes of enemies upon which the challenge and fun of the game relies becomes less of a creative task and more of a…daunting one. I did get to have fun with it, inventing new flavour skills and item drops as I went, but at some point I felt there were too many enemies to deal with. And I don’t know how much of an impact it made on the overall feel of the game to give each enemy a special set of attributes.

Placing a few new numbers in the item table, putting in some creative names, thinking up scenarios where that item will appear—that was enjoyable. I have a lot of fun doing small, menial tasks where the constraints are dictated by my imagination. It’s not that there is no goal. The goal is just to fill out all the item details. However, the rules can be transmogrified to my liking to create a mind puzzle that suits me. You could say that I like being the one making the rules.

Maybe I’ve decided that one class will have the very worst and best abilities at two different points in the game. Maybe I’ve set it upon myself to place one skill instructor in every forest, each teaching two skills, with one being elemental (with no element overlap). Perhaps I make it a rule that each shopkeeper will sell exactly one bow, but each different and with predesignated attributes that I must not change (unless I get stuck). And then, like a Sudoku board, I must fill in the rest around what I’ve put in place in a way that makes sense. And I create more of these constraints until the answer sort of reveals itself.

Do these rules make things more fun for the player, or are they just fun for me? I don’t know. What I will say is that we both got a game out of it.